|

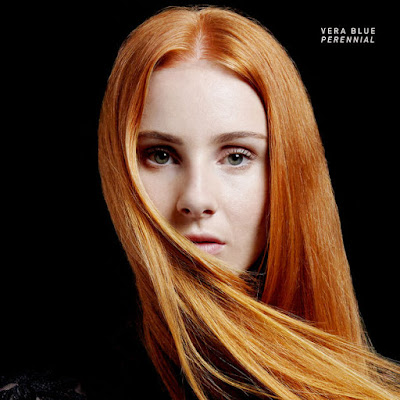

Universal | iTunes.com |

· · ·

Lana del Rey casts a long, cold shadow over the fertile gardens of indie folk music. In a luxurious perfumed haze of heroin and clove cigarettes, she and her elegant discography recline languidly on some postcard-perfect beach, tresses of deep brunette rippling in the salty sea breeze. She is the image of glamorous Americana. And she has sucked up every last drop of humidity in the air. In her gauzy wake, sproutlets must subsist on altogether stranger nourishment.

Father John Misty refused point-blank to adapt, his inner acidity bleeding him bone-dry. Caustic alkaline deposits rehydrated Daughter’s luscious maximalism ammonia-clear. Aurora activated her contingency plan — Scandinavians thrive in darkness, after all — and drank down the starglow dripping from high above. But between the sturdy oaken husks, the shimmering crystalline succulents and the ink-black lilies, Vera Blue sent roots digging deep into the rich, dark soil. And they happened across a power line.

Perennial is quite the bouquet.

Vera Blue, the new project from The Voice alumna Celia Pavey, sparks up folksy guitar noodling with supercharged synthesisers and overvolted affection for contemporary pop music.

Her own sultry tones are the main attraction of Perennial, be they refracted through an organic vocoder, accompanied by a chorus of warped clones, or clean and unadulterated. Celia throws up electronic confetti, a sprinkle of pixel pollen high-hats that alights on smoother, fibrous lengths and on jagged, spiny edges alike.

Embedded in the rind of Perennial is a familiar knot of fallow anxieties and disappointments, the necessary prerequisites for the regrowth suggested by the album’s title. Celia pens a lean, direct narrative, unencumbered by much in the way of metaphor. She does not indulge in long-form specificity like Lana or Father John are wont to do. The single exception comes in the form of a farewell to an ex’s mother hung with looplets of pessimism, a stalk of lavender strung with pulsing diodes. Still, Celia’s vague use of language tends to frustrate. “Whoever said it was better to love and to lose / Has obviously never loved anyone” is as pithy as Perennial gets.

Her strengths instead take the form of shapes and lines: off-kilter rhythms assigned with angular precision (the zig-zagging chorus of ‘Fools’), tongue-in-cheek observations deployed with the stutter of a diva (“I shouldn’t have to use / My lady lady lady lady powers”). And consequently, she is at her best when she is at her biggest. Sometimes in the quiet she loses the forest for the trees, but Perennial’s poppiest moments amplify Celia’s peculiarities skyward. ‘Private’ spreads its fractal vines, ‘Overachiever’ coils robustly into wreaths, and album highlight ‘Magazine’ erupts into serrated thorny stabs.

Lana del Rey may blot out the sun with her flower crowns and dark chocolate cherries, but nothing can stem the flow of the synthetic chlorophyll that pulses through Celia’s veins.